Grieving Death

We must all cope with the death of others: family, friends, and acquaintances. But doing so, beyond social mourning rituals, is often hidden in our private feelings of grief.

Image by kalhh from Pixabay

We all grieve in response to loss. These days, as I binge-watch 25-year-old episodes of The West Wing, I grieve the loss of democracy and the rule of law that the current regime has imposed on the U.S. This feeling is very unpleasant, akin to the feeling of confusion and emptiness that I have often experienced upon the death of family members and friends.

Of course, as individuals, we all grieve differently. Some might think my nostalgia for past political eras is naïve, a refusal to accept what needs to be done to “make America great again.” And some people who have endured unspeakable abuse at the hands of family members or other authoritative figures might feel a sense of relief at their demise. I cannot speak for everyone.

As I’ve grown older, however, I find that significant loss of a job, status, or close relationships often provokes disparate, even conflicting, emotions. We might be happy about not having to attend boring, pointless meetings, but losing the social interaction that being employed provides might make retirement feel lonely.

Emotions following the death of a family member – parent, sibling, child, or spouse – can be even more conflicted. Escaping control of an abusive parent or spouse is surely welcome, but such figures are also important witnesses of our lives who have given shape and meaning, no matter how twisted, to our existence. I have sometimes overheard remarks such as, “I’m glad that he’s finally gone, but I miss him.”

“Stages” of Grief

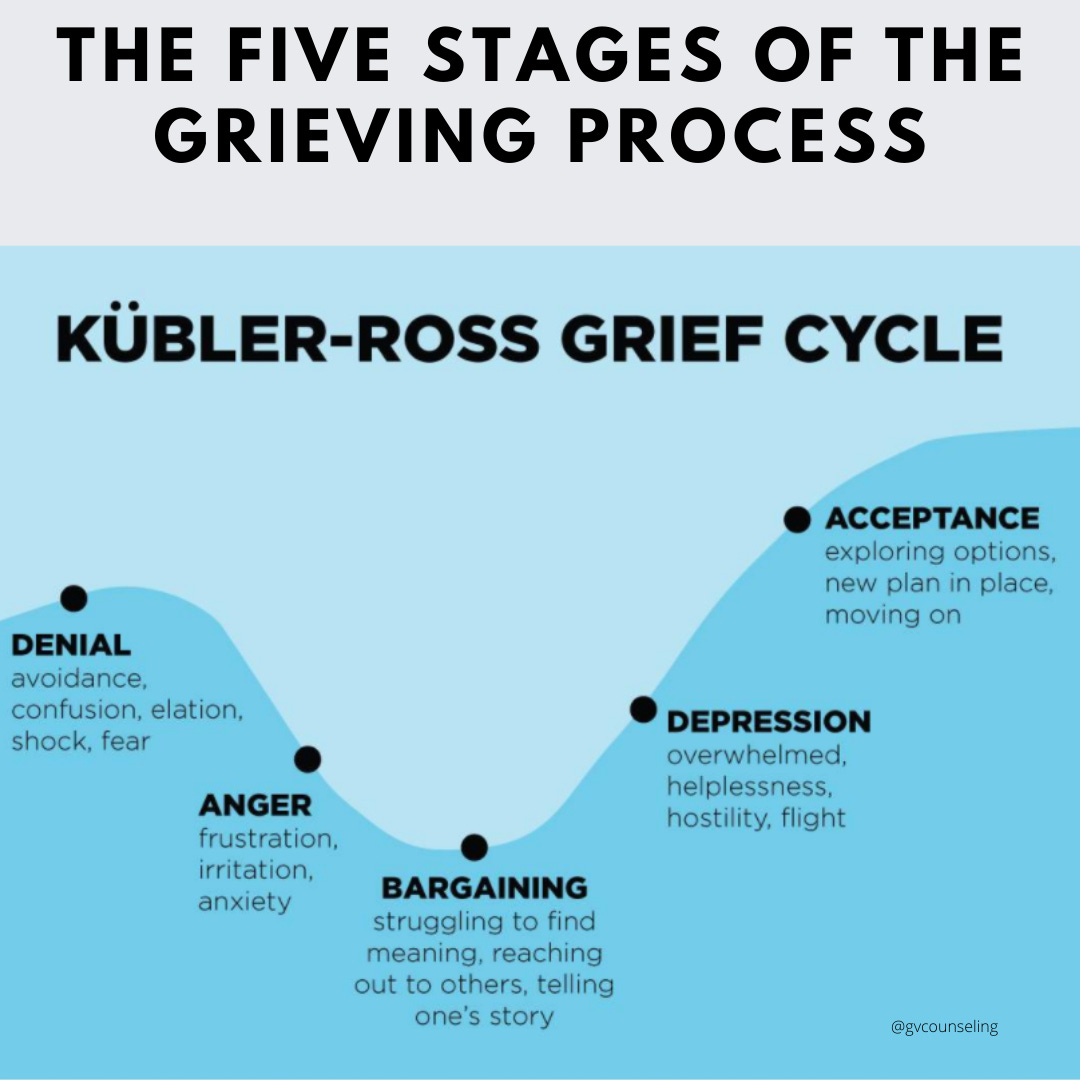

Forty years ago, when I was teaching a college course on “Death and Dying,” the most common way of thinking about grief used the model of five stages as developed by Elizabeth Kübler-Ross in her book, On Death and Dying (1969): Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and Acceptance.

Most people interpret these stages as linear points on a journey, however long, through each stage to eventually achieving “acceptance” of the reality of dying or death.

However, Kübler-Ross never intended these stages to represent fixed progression toward a final goal of peace. She held that each of the stages could be experienced in a different sequence, for varying lengths of time, or not at all. Her caution matches my own experience.[1]

Grief and Life Stories

Grief is an experience that is both universal and unique. We all grieve at various points of loss, and we all do that in our own way.

As I look back over my life, I find that I continually recall, edit, and revise chapters in what has turned out to be my life’s story. Mostly, these chapters exist as an oral tradition or remembrances in my own head. And it is through such narrative that I can touch meaning.

This is why I’m drawn to Robert Neimeyer’s meaning-making and reconstruction model of understanding the impact of loss and the response of grief.[2] When I apply that model to my own experience, I find that my grief over the losses in my life has become a never-ending process – a process of continually reconstructing a sense of meaning and purpose.

At times, it has involved profound depression. At other times, feelings of anger became nearly overwhelming. And at still other times, a sense of renewed, though different, meaning has arisen. Taken together, the life stories and the grieving embedded in them amount to an emotional witch’s brew.

Grieving Death

My most profound and longest-lasting encounter with grief began with the death of my parents in 1991. Until then, I had faced only the deaths of my grandparents, some distant relatives, and a few friends. Losing my parents was a uniquely challenging event.

I vividly remember their celebration of their 50th wedding anniversary in 1989. They were in reasonably good health and were joined by their siblings and spouses, my cousins, and many friends and former students. It was a genuinely happy occasion. I could not anticipate that my parents and their entire generation of the family would be gone within just a few years.

By 1990, my father’s prostate cancer had metastasized into his bones and led to his dying after much suffering in July 1991. My mother’s renal cell cancer had also returned and infected her liver. She died in November. And my father’s sister (a second mother to me) died of heart failure in January 1992. I delivered the eulogy at each of their funerals.

That much loss threw me into an emotional tailspin. Despite having to compose the eulogies, I remember almost nothing of the social mourning rituals. Literally in shock, I took a month’s leave from my dean’s position in December to handle my parents’ estate and begin therapy. Although I recall being puzzled at how the Christmas season could proceed for everyone as if nothing had happened, I don’t recall being in a state of denial or anger – just profoundly depressed.

Despite my earning a Ph.D. degree in religion and teaching college courses in religious studies, I was not particularly religious in any traditional sense. I had no religious framework to help make sense out of my radically altered life story.

Fortunately, my therapist had studied philosophy at a graduate level in addition to psychology. That allowed us to have rather intense discussions of Buddhist notions of the impermanence of things and how meaning can still emerge in experience. And he helped me to anticipate that such questions would now become an enduring undertone to my life experience – as they have.

My Parents’ Legacy

Although remembrances of other friends and distant relatives who have died occasionally come to mind, I did not anticipate that I would think about my parents or aunts and uncles several times each day for the past 34 years. Does that make my grief another case of what some therapists call “complicated grief?” I think not.

Rather, my memories of my parents – many humorous anecdotes, others that are somberly nostalgic – comprise a large portion of the basic structure of my life story. From them, I received a fundamentally even-keeled outlook on life. Over time, I have become more overtly emotionally related to others, especially toward my wife, but not in a volatile, up-and-down sense. Things were not always that way.

Immediately after their death, I became deeply depressed with extreme peaks and valleys of emotional outbursts. Once again (repeating how I coped after a divorce), I listened to the symphonies of Gustaf Mahler. Mahler’s combination of intensely dark emotional themes interspersed with some of the most delightfully elegant melodies has always reflected the ambiguity of life for me without words.

I also reread the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, S.J., which is realistically hopeful without being pollyannaish. Among others, his poem, God’s Grandeur, was especially significant, perhaps because he, too, wrestled with depression and fundamental questions of faith.

Today, I find myself reflecting on what I learned from my father about what it means to be responsible, both for myself and for others. And in dealing with that question in my life now, I’m mindful that, while doing his best in teaching mathematics or coaching athletic teams, he had overemphasized responsibility as a virtue. (My therapist told me that I needed to dial that back a little!)

My mother’s legacy to me was rather different. I never heard her say anything disparaging about anyone. Occasionally, she expressed an inability to understand someone’s actions if they annoyed her. She also provided a model for retaining a sense of beauty in the face of disappointment.

As a classical pianist, she had played for a community orchestra and had ambitions to make that her career. Life got in the way, however, and she eventually became an elementary school teacher. She once mentioned to me that she was deeply disappointed by that turn of events. She also offered piano lessons to local children. I still remember her sitting at her piano playing the music of Frédéric Chopin or Franz Liszt for her own enjoyment. Today, I listen to Chopin, Liszt, and others to recharge my wonderment at the beauty that stubbornly accompanies our lives.

Grieving Today

As I’ve grown older, I’ve encountered the death of friends and colleagues more frequently. While I remember them fondly, I continue to remain distrustful of any cosmic purpose for life – for myself or others. For me, grief (and social mourning) has not brought “closure.” Memories of lost loved ones remain clear, and sadness at permanent separation remains intense.

Grief provoked by death, however, has caused major changes in my worldview. I believe that meaning in our lives must be created by ourselves in company with one another. My life’s narrative, therefore, must be provisional, even an improvisation. Sharing our stories is one way (perhaps the best way?) of facing what comes next. My wife’s ability to share her own story and to listen to mine has been vital to my retaining a sense of meaning and purpose.

As mentioned in my introduction, grief over death is not the only kind of grief. We also grieve over non-death events. That topic will be addressed in a subsequent installment.

If you are grieving or you know someone who is, I strongly urge you to watch the video that is linked in Note 2 below.

In the meantime, I would appreciate learning about your own encounters with grief should you care to share them. After all, we’re in this together.

NOTES

[1] Tyrrell P, Harberger S, Schoo C, et al. Kubler-Ross Stages of Dying and Subsequent Models of Grief. [Updated 2023 Feb 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507885/.

[2] For an accessible explanation of Robert Neimeyer’s approach along with revelations about his own grieving, please watch Lesel Dawson’s recent interview with him. It’s about 48 minutes long, but worth your time if these issues concern you.

I conduct research for these posts so you don’t have to.

I have therefore activated the paid subscription option.

I know that many authors ask you to sign up for a paid subscription. If you cannot, I understand. All posts will remain free.

But if you have the means, please be aware that an annual subscription works out to only $4.17 per month and will entitle you to additional features and content (podcasts, online interviews, live chats) as the newsletter develops.